RUMAH Degil was built in 1926 in Jalan Chow Kit, a stronghold of the Mandailing community at the time. The house was a stubborn remnant of a time long past, hence its name.

Rumah Degil survived the Japanese occupation, Communist insurgency, May 13 riots and even the transformation of Chow Kit from a village with similar houses on either side to a commercial centre and rather shady district with its fair share of drug addicts and prostitutes. But it finally fell to the forces of commercialisation when the family who owned it sold it to developers.

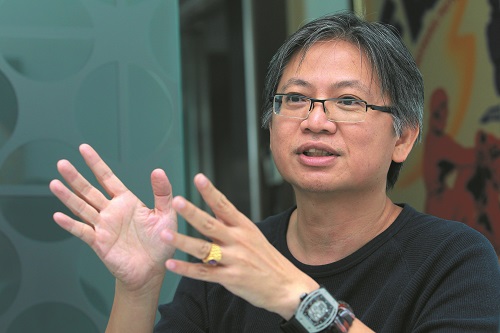

The restoration story began when a contractor approached architect K C Tan (pictured, below) to take a look at a project in Chow Kit in late 2014. He showed up at the site and was horrified to find that the project involved dismantling a charming kampung house and building a shopoffice on the site.

“I knew the significance of the place. My grandparents had lived practically opposite it, in another kampung house. Chow Kit had been a development of kampung houses and slowly but surely it had transformed over the years,” he says.

Tan convinced the contractor that it would be a shame to tear it down and sell it for scrap so it ended up as chairs and tables in yet another hipster café. He had a gut feeling about the place, although at the time, he didn’t know much about it. He was busy with plenty of other projects and knew that saving this one would have to be done on a voluntary basis.

So, he roped in his cousin James Chong who, like him, had been born in Jalan Chow Kit. Tan would handle the architectural aspects of dismantling and reconstructing the house and Chong, a consultant who provided advisory services and launched businesses, would handle the research and marketing.

Chong began to research the background of the house, but hit a brick wall. He tried talking to real estate agents, but they couldn’t connect him with the previous owners. He asked around the neighbourhood, but nobody could tell him anything.

“When you are trying to preserve something, you need to go beyond the structure to the story behind it,” he says.

After six months of no results, the contractor suddenly sent him an article by Utusan Malaysia that mentioned the house. “When I read it, it was like opening a box and peeking in. The article mentioned Sutan Puasa and the fact that it was a heritage building. So I kept researching and stumbled on an article about an award-winning video by a student on the house, which I found out was called Rumah Degil.”

Chong knew he had to see the documentary. It would probably be hidden somewhere online — and he found it. “It was a goosebump moment when I realised it was the same house. I frantically tried to find out who shot the video that ended up in Vimeo and got Fatul’s name.”

Fatulrahman Ghazali had shot the film in 2007, interviewing the old grandmother who lived there at the time. Chong wrote to Fatul and they spoke on the phone. “It was like yes, yes, yes, we want to do this. We were both very excited.”

Chong was also pursuing another line of research. He had found an obscure reference to Sutan Puasa when he was researching the house and he found an academic article that had been written on the founding of Kuala Lumpur. “The paper argued that Sutan Puasa was the earlier founder of KL and the last part of the article mentioned that his last remaining legacy was a house in Chow Kit. So I was like, it must be this one.”

Chong was also pursuing another line of research. He had found an obscure reference to Sutan Puasa when he was researching the house and he found an academic article that had been written on the founding of Kuala Lumpur. “The paper argued that Sutan Puasa was the earlier founder of KL and the last part of the article mentioned that his last remaining legacy was a house in Chow Kit. So I was like, it must be this one.”

The paper was written by Abdur Razzaq Lubis, a student of social and cultural anthropology and author of numerous books on the Mandailings in Malaya. Chong managed to rope in Lubis as consulting historian and his wife Khoo Salma Nasution.

Khoo Salma, in turn, brought in Dr Gwynn Jenkins, who had worked on the restoration of Suffolk House in Penang. The two later came on board as conservation advisers.

The last member of the team was Andrew Lee, founder of ARCH and the Kuala Lumpur City Gallery, who came in as commercial adviser. “If we are going to rebuild the house, how are we going to make it self-sustaining so it does not go into disrepair and has to rely too much on grants and stuff like that,” he says.

Chong expounds on Lubis’ theories about the founding of KL. “The history of the city is actually divided into two phases — the post-Klang Wars in the 1870s and period before that. Most of our history comes after that, when the Selangor sultanate had been established and Yap Ah Loy was the third Kapitan Cina.

“It is arguable that Raja Abdullah founded KL because he was based in Klang. He sent some coolies up to KL to look for tin, so he did not come to KL himself. And there was already a settlement there,” he points out.

This is where it gets a bit tricky. “What is the definition of founding? The first settlers or the first commercial activities or the ones causing the expansion? Lubis writes that even before Yap Ah Loy showed up, there was already a thriving village and Sutan Puasa was the one who turned the village into a thriving commercial centre. He was also the one who brought the Chinese in,” says Chong.

“Lubis argues that he had built that little village and turned it into a commercial centre. Therefore, Sutan Puasa should be recognised as one of the earlier founders of KL.”

Fast forward to the Klang Wars, which Chong says was actually a war between the Mandailings and the Bugis. “Before the war, the Mandailings had a fortress on Bukit Nanas.”

Tan cuts in. “Imagine the land between Masjid Jamek and St John’s Institution without all the buildings. That is a very strategic hill overlooking the confluence of Sungai Klang and Sungai Gombak. In the old days, the rulers always took the higher ground for protective reasons. It is called Bukit Nanas because they planted pineapples on the hill to stop their enemies from creeping in, like a bush fence.”

Having taken on the preservation of Rumah Degil, or Rumah Pusaka Chow Kit (Chow Kit Heritage House), as it is now called, the team wants to do things properly. The project has three parts, says Chong.

“One is rebuilding the house and turning it into more than just a monument to the past. We want to turn it into a space where you can create things for the future, but in an environment that respects and remembers our past.

“We didn’t want it to be just rebuilding a house so it looks nice. Even the word ‘museum’ has a bit of a negative connotation to it. It is a museum by nature, but it is a museum where you are a part of it — you really experience it.”

The second part is recording the history of the house and surrounding areas, which are inextricably linked to the history of KL. “The recording of history is where Fatul comes in. He will do interviews with people who used to live in KL, find out about the inter-racial dynamics — what they used to do and how they worked with each other.”

Chong thinks this part could be a project on its own and they could get funding for it, which could be channelled towards the restoration of Rumah Degil.

The third part will be to produce a website or an app that compiles all the information and interviews they have collected to help the visitors who move through the house really get a sense of the history of the house — and of the city as well.

“We are looking at a multi-use design structure for the space around the house to turn it into a creative hub so that activities can be done around the house. We will have shops to help sustain it,” says Chong.

“And K C [Tan] came up with the idea of rebuilding the house in such a way that it mirrors its last recognisable look. So, we will build a false front to let people recognise that it was Chow Kit. We are looking at duplicating the existing building, but we are taking the signage further back to give it that retro feel.”

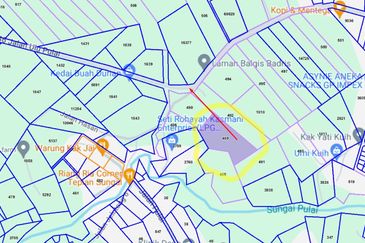

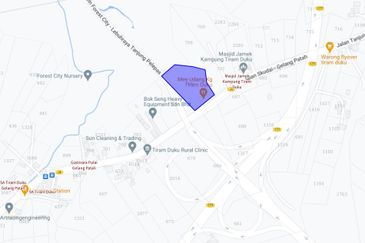

The team is looking for someone who can contribute a piece of land to the project. “We will be contacting DBKL (Kuala Lumpur City Hall) to see whether it has any land that it can put up. We are trying to find a place around Masjid Jamek that is maybe 15,000 sq ft, which tourists can actually walk to,” he says.

There is a greater purpose here. “There is a soul to KL. It is hidden and nobody really sees it. Part of this project is to rekindle that,” says Chong.

“KL developed from the contributions of multiple races, from the Mandailings to the Chinese labourers to the Indians. We all merged together to build this city, like what this house has been through. That is the narrative we want to get through.”

Start your search for a condominium of your choice HERE.

This article first appeared in the Special Report Rejuvenating Cities Together, of The Edge Malaysia Weekly, on March 28, 2016. Subscribe here for your personal copy.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Seksyen 8, Kota Damansara

Kota Damansara, Selangor

Seksyen 5, Kota Damansara

Kota Damansara, Selangor

Jalan Persisiran Laman Setia, Taman Laman Setia

Gelang Patah, Johor

Cubic Botanical

Pantai Dalam/Kerinchi, Kuala Lumpur

Millerz Square

Jalan Klang Lama (Old Klang Road), Kuala Lumpur