JUST last week, Perda City Mall in Bukit Mertajam, Penang, suddenly shut down after a mere 18 months in business. The mall’s operator gave tenants a day’s notice in writing and no explanation, according to people familiar with the matter.

Last month, Sime Darby Property Bhd and CapitaLand Malls Asia’s joint venture — the RM670 million Melawati Mall in Kuala Lumpur — postponed its opening from the year’s end to 2Q2017. The delay was due to “design planning and current headwinds” in the economy.

Recall too that last year, two malls in the Klang Valley — SStwo Mall in Selangor and Bukit Bintang Plaza in Kuala Lumpur — closed down for redevelopment while the massive 2.3 million sq ft net lettable area (NLA) Empire City Mall in Damansara Perdana, Selangor, announced that it would delay its opening from end-2015 to next month.

Are these signs of the times that are to come? Perhaps.

The shopping mall business has come under pressure and undergone substantial changes in recent times due to a confluence of external factors. They include the much-talked-about oversupply of retail space, lower tourist arrivals, weakness in domestic retail spend, lacklustre consumer sentiment, intense competition for tenants and changing consumer preferences and behaviour.

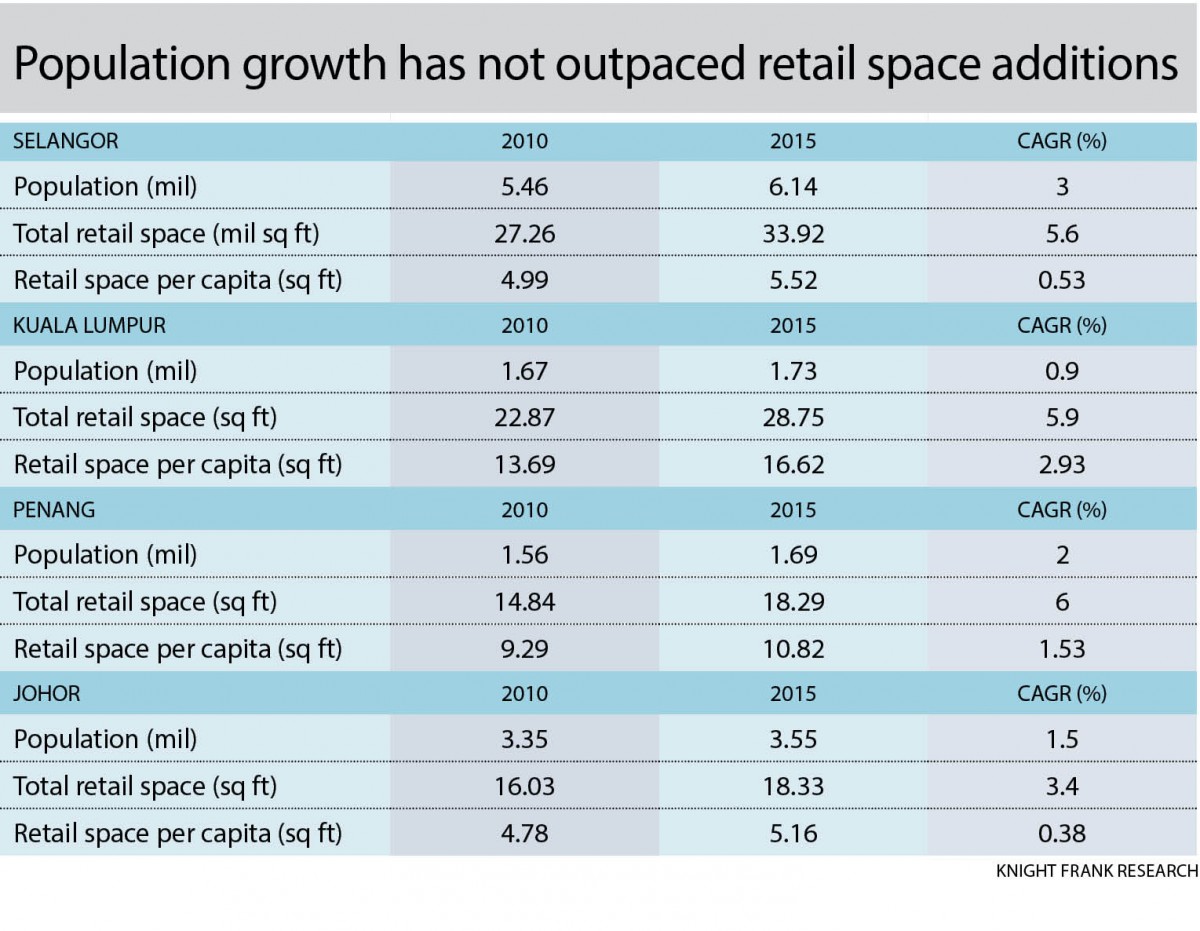

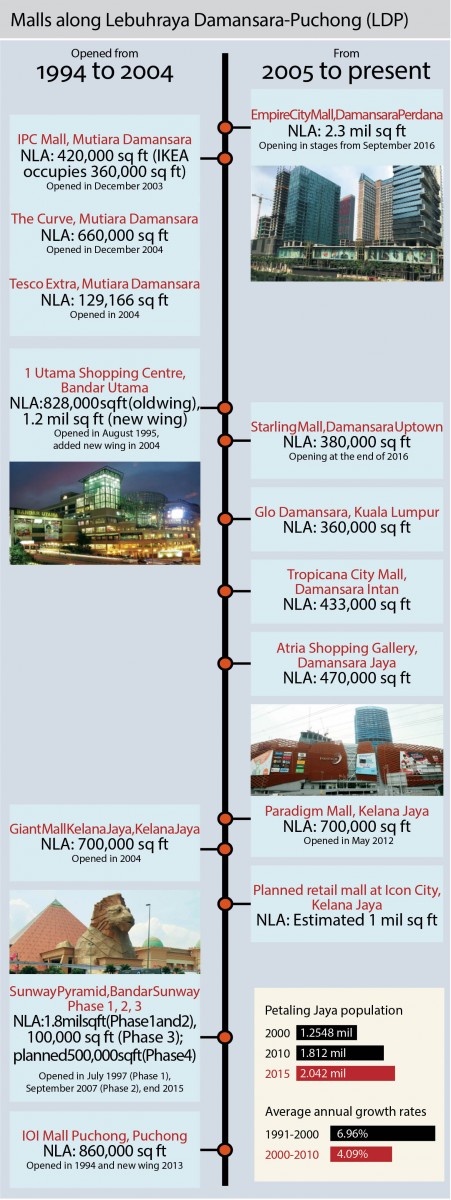

Data from the National Property Information Centre (Napic) reveals that Malaysia had 148.85 million sq ft of existing retail space with another 16.2 million sq ft incoming and a further 11.08 million sq ft being planned as at end-2015.

According to Henry Butcher Malaysia Sdn Bhd, the Klang Valley (covering Kuala Lumpur, Selangor and Putrajaya) had 241 shopping centres with a total space of 64.1 million sq ft, with an average occupancy of 80.4% in the same period.

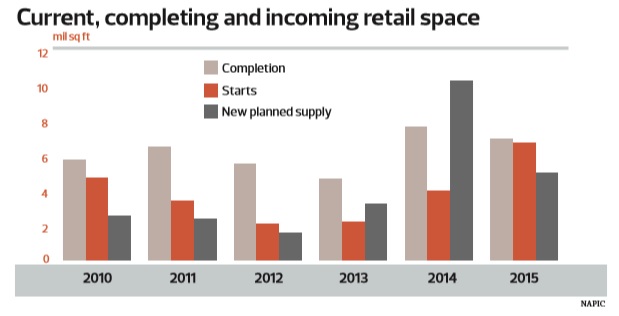

The saturation is mostly seen in certain locations in the Klang Valley, particularly the Damansara area. Malls in the Damansara area include 1 Utama Shopping Centre, Glo Damansara and Atria Shopping Gallery, with a few more to open in the coming months to next year, such as Empire City Mall, the Starling and Damansara City Mall.

What’s more, shopping malls are on the front line of confronting weak consumer sentiment and lower retail spend due to macroeconomic pressures such as the weaker ringgit, which translates into higher costs of goods and services.

The Malaysian retail industry reported a 4.4% year-on-year drop in sales in 1Q2016, compared with 4.6% growth in 1Q2015, which was buoyed by pre-Goods and Services Tax buying, according to survey data from the Retail Group Malaysia. This prompted it to revise downwards its sales growth projection to 3.5% from the earlier 4% for 2016.

What does this all mean for malls?

Most retail consultants say they cannot remember a more challenging time for shopping malls in the country. Among them are Savills Malaysia managing director Allan Soo, who recalls that the difficult times during 1997/98 Asian financial crisis were real but temporary for the retail industry.

“After 1998, things were back up pretty fast,” he says. Recall that some major malls opened almost immediately after the crisis, including Suria KLCC (opened in May 1998) and Mid Valley Megamall (November 1999).

“This time is the toughest. There are more variables, more competition and real oversupply issues. It’s going to be much harder work,” adds Soo.

Industry experts say these dynamics are unlikely to significantly dent the business of well-managed, established malls in locations where there is already a big catchment. The oft-cited retail giants include 1 Utama, Mid Valley Megamall, Suria KLCC, Pavilion Kuala Lumpur and Sunway Pyramid.

Suria KLCC CEO Andrew Brien concedes that consumer sentiment has been weaker across Asia. To mitigate that, he says Suria KLCC is leveraging its fundamental strength, chiefly its location, access to customers, footfall and market understanding.

“Our strategy is consumer-centric, by continuously understanding and actively responding to our consumers and retail partners,” says Brien.

Relatively insulated too are the well-managed shopping malls in tier-two cities outside the Klang Valley, such as those in Perak, Penang and Johor.

Nevertheless, newcomers to the mall game will find it increasingly tough to attract shoppers and preferred tenants.

Power dynamic shift from landlords

What’s for sure is that the good old days of “build and they will come” are long gone and mall owners can no longer sit quietly and wait to collect rent.

Sunway Real Estate Investment Trust CEO Datuk Jeffrey Ng says that it is now a tenant’s market and landlords have to play a supportive role to tenants, especially when the economy proves challenging.

This means the landlord is no longer a mere rent collector but an active business partner who has to help drive business. Landlords no have to play their part in running lots of on-ground activities to attract consumers to the mall and directly assisting tenants in coordinating sales and promotional activities.

A good asset manager is an active manager who knows how to add value. “Good asset managers spend on improving tenant mix and bringing in the traffic, not just cosmetic enhancements,” says a retail consultant who declined to be named.

Given the growing supply of retail malls in Malaysia, Sunway REIT’s Ng points out that tenancy mix and offerings are becoming more similar. This could lead to market share dilution for existing players while the newer ones that cannot differentiate themselves may find it hard to sustain footfall after the novelty wears off.

Mall operators and retailers will have to work harder to attract shoppers and reach out to previously untapped or under-served segments.

“Many shopping centre owners had to offer rental rebates in order to retain tenants while many new shopping centre managers needed to extend rent-free periods for tenants as it took longer to draw shoppers to their centres,” Henry Butcher Malaysia says in a report.

Compared with decades ago, the rental structure has undergone changes in recent years. These days, a tenant can be charged different modes of rent. It may be a fixed amount along with service charges, base rental plus a percentage of a tenant’s turnover, or base rental or a percentage of turnover, whichever is higher.

“Today, the rental structure goes by negotiation between the landlord and tenant. Who needs who more? Do you need a particular preferred tenant to attract customers to your mall? Or does a tenant absolutely need to open in your mall?” says retail consultant Richard Chan of RCMC Sdn Bhd.

It is not necessarily true that a Grade A tenant — also known as a crowd-puller — pays the highest rent. Most times, preferred tenants pay preferred rental rates and get preferential terms. Strong tenants also have the upper hand in negotiating competitive terms against weaker landlords. For example, a major bookstore chain can demand to be the only bookshop in the mall.

Mall operators say some tenants, especially the preferred mini anchors, are also beginning to ask for capital expenditure, where the landlord has to pay for renovations.

Going by turnover rental, the shopping mall operator is indeed a business partner of sorts for tenants and is incentivised to work harder to drive business for the tenants. But it cuts both ways as the landlord takes on more risks, because it accepts the potential volatilities of retail sales, says an industry player.

According to Henry Butcher Malaysia’s data, occupancy and average rental rates for Kuala Lumpur and Selangor malls somewhat suffered last year.

Average monthly rental rates, excluding the anchor tenants’, fell 7.2% to RM13.03 psf to RM12.09 psf in Kuala Lumpur but held steady at RM10.12 in Selangor.

Average occupancy for Kuala Lumpur malls fell to 82% from 83.2% in 2014 while Selangor malls saw a decline to 79% from 81.7%.

According to Sunway REIT’s Ng, leading retail malls may not see lower rental rates despite the challenging operating landscape.

“Established malls with strong track records should remain resilient and profitable, albeit growing at a slower pace. The challenge lies in the newer malls where some are offering extensive incentives to boost occupancy, and supporting tenants will need a longer gestation period,” he says.

According to RCMC’s Chan, yields of 6% to 8% is considered decent, given the competitiveness of the industry compared with the good days where mall owners can expect yields of 15% to 20% or more.

Rent is certainly the bulk of a mall owner’s income, but increasingly, ancillary income from mall management is becoming important too. Apart from floor rental space, malls can make money from things like service charge, utility management, car park management, kiosk and pushcart rentals, promotional and al fresco areas as well as advertising and signages. “It can be as high as 20% to 30% of total income if you manage it well,” says Chan.

Not all doom and gloom

Despite the more challenging times, Savills Malaysia’s Soo reminds that things are not all doom and gloom. Sure, it is becoming more difficult to create another giant like Suria KLCC or Mid Valley Megamall.

“There are opportunities as well. Everyone is trying to refine their game and strategy,” says Soo.

According to him, despite the challenges, there are still opportunities to build and operate malls profitably, provided that they are well planned from the start and the management is competent.

In an intensely competitive area, what becomes extremely important is in the planning of the mall and conceptualising a differentiating factor.

“Assuming [in a certain area], all the external factors are the same, then internally, you have to be able to say ‘I am the biggest’ or ‘I am the best’,” Soo says.

Retail consultants say the key to developing a successful shopping mall is to go back to basics and understand the needs and wants of a mall’s primary catchment area. This means understanding the demographics, spending power and lifestyle demands.

“Shopping is no longer about going somewhere to buy something. It is all about the experience,” says Soo.

Retail is hardly a static environment and consumer preferences are constantly evolving due to a number of factors, including higher levels of education and income, aspiration, lifestyle preferences, the prevalence of e-commerce and social media-driven consumption behaviours.

Additionally, technology can be a key driver of traffic and consequently, consumer spend. Social media platforms are becoming more important in attracting and retaining customers. Data analytics, too, is a useful tool for mall managers.

According to Soo, the mass rapid transit will be another catalyst for shopping malls as it will help improve accessibility for locations along or near the MRT line. “You can see that effect throughout the world. Every time an MRT line is built, sales improve or a mall makes a comeback. Malls are driven by footfall; if you get more footfall, you get more business.”

There are still opportunities for shopping malls in new townships or tier-two cities across the country where there is pent-up demand for retail experiences.

One example of a successful mall in a tier-two town is Kluang Mall in Johor, which is owned and operated by property developer Majupadu Development Sdn Bhd.

Despite the challenges in 2015, Majupadu executive director Tey Fui Kien says, the mall saw a record 5.7 million visitors, with an average 10% y-o-y increase in traffic.

She attributes this surge in visitors to the mall’s four new fast fashion mini anchors — H&M, Uniqlo, Cotton On and Brands Outlet — which came in at the end of last year.

“Tenant sales have increased across the board with a number of retailers recording double-digit growth,” she says.

Kluang Mall, however, is not facing the same competitive pressures as malls in the Klang Valley. There are no large malls that directly compete with it in central Johor. Its primary catchment has 314,000 people within the Kluang District and a larger catchment of 700,000 within a 45-minute drive.

“A lot of people now shop at Kluang Mall instead of driving 90 minutes to Johor Baru. It reinforces our point that retail is largely driven by the local catchment and demographics,” says Tey.

The mall bandwagon runs into headwinds

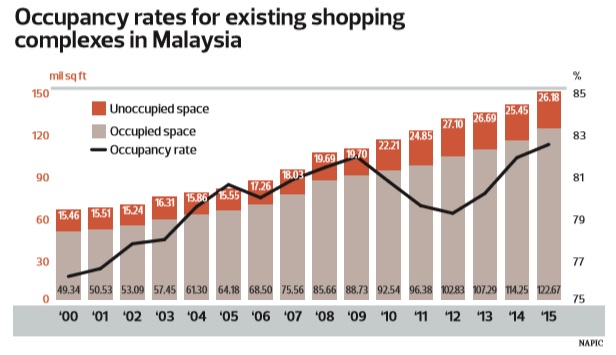

Shopping malls have been the assets en vogue of late. Data from the National Property Information Centre (Napic) shows a spike in new planned supply of retail space from 2012.

New planned supply of mall space doubled from 1.6 million sq ft in 2012 to 3.2 million sq ft in 2013. Then came the surge to 10.23 million sq ft in 2014, before halving to about five million sq ft in 2015, likely due to economic uncertainties.

In recent years, both property developers and construction companies have been coveting shopping malls.

Listed companies that currently own malls include Mah Sing Bhd (Star Avenue Lifestyle Mall in Sungai Buloh), UEM Sunrise Bhd (Publika Shopping Gallery in Solaris Dutamas, KL), Glomac Bhd (Glo Damansara, KL), OSK Holdings Bhd (Atria Shopping Gallery, Damansara Jaya), JAKS Resources Bhd (The Evolve Concept Mall, Ara Damansara) and PPB Group Bhd (Cheras Leisure Mall, KL).

Then, there are the privately held property and construction firms that own shopping malls: First Nationwide Group (1 Utama Shopping Centre in Bandar Utama, Selangor), Mammoth Empire Holdings Sdn Bhd (Empire Shopping Gallery in Subang Jaya and developing the Empire City Mall in Damansara Perdana), See Hoy Chan Sdn Bhd (developing The Starling in Damansara Uptown) … and the list goes on.

Industry observers say this desire to own shopping malls is driven by the realisation that recurring income from retail assets is a good thing to have, especially when property development or construction earnings are impacted in a downturn.

The caveat, however, is that the bigger property players may not see meaningful contribution to their earnings from shopping malls; their revenue base may be so large that the income from one or two malls may be relatively small. Furthermore, some of the mall assets are still in the early years of operations.

Costly land also means that property developers are likely to push for high plot ratios on a relatively small plot to maximise returns on development.

Many property developers build shopping malls as part of integrated developments. For example, Eco World Development Group Bhd’s joint-venture Bukit Bintang City Centre, which has a gross development value of RM8 billion, boasts a lifestyle mall to complement its office towers, serviced residences and hotel.

I-Bhd, meanwhile, is constructing a one million sq ft NLA shopping centre at a gross development cost of RM799 million as part of its Central i-City project.

Tropicana Corp Bhd’s three projects also feature malls, namely in its integrated development Tropicana Gardens, the Tropicana Metropark township in Subang Jaya and the Tropicana Danga Bay development in Johor.Tropicana used to own Tropicana City Mall but sold it along with the Tropicana City Office Tower to CapitaLand Malaysia Mall Trust for RM540 million cash in 2015.

The general thinking seems to be that if there are high-rise serviced apartments, hotels and offices, there must be demand for a mall.

But Savills Malaysia managing director Allan Soo says it is not a good idea to just rely on the population of an integrated development to sustain a mall, unless it is sufficiently large, like a township or an urban centre.

“You can’t support a mall with 1,000 people living in a condominium. You need a whole population. It’s about the 5, 10 and 15-minute-drive catchment areas.

“It is not that having apartments there is no good; it’s a good thing. But it’s also about the amount of traffic that could potentially come. The whole place has to be an urban centre,,” he adds.

According to Soo, the first thing retail consultants do before planning a mall is to do an assessment to understand how well a particular market can support a mall.

Broadly speaking, a 300,000 sq ft to 500,000 sq ft mall needs a minimum market of 200,000 to 300,000 people. A larger mall will have to be in the vicinity of much larger primary and secondary catchment areas.

Apart from population size, income levels are also an important gauge of a key market’s spending power and habits. “You want a primary income level of at least RM5,000 a month household average because if it is below that, it is hard to do anything that is competitive,” Soo says.

He adds that the next thing to evaluate is how well retailers are doing in the vicinity of the proposed mall. “If all the retailers are not doing well, then it is hard for you to justify building a mall unless you know there is potential or maybe the retailers there are not doing the business properly.

“For example, if you discover that the retailers can make roughly RM200 psf turnover a month, and if you work backwards, you can do RM15 or RM20 psf on rent, then you know there is capacity for a mall. Then you can work backwards and size the mall, the tenant base, the positioning, everything.”

With the property market in a prolonged slowdown, can retail assets be the buffer?

Not really, say the experts.

One retail consultant laments, “Sure, a lot of developers want to own malls. But a lot of them are used to the ‘build-to-sell’ mode as opposed to build-and-lease, which is the mall business. This is a very different game.”

The shopping mall business in Malaysia has become increasingly challenging over the years, according to industry veterans. This is due to a combination of factors, including the rising cost of construction and operations coinciding with pressures on rental and occupancy rates.

Soo, an experienced retail consultant, points out that asset yield-on-cost is facing pressure because total development cost, particularly land and construction cost, has outpaced rental growth.

“In the past, costs didn’t rise so fast and rents were still strong. There was no oversupply; a bit of saturation in some areas but not so hard. Initially, yield on cost was high, in the high teens. Today, you’ll be lucky to get about 11% in the first year of operation, assuming full occupancy,” he says.

It generally takes some time for new malls to start charging rank rent or the highest level of rent possible for a certain area. There is typically a 20% to 30% discount to an area’s rank rent.

Secondly, says Soo, it is getting increasingly difficult to get a new mall leased up to over 80% when it opens its doors. It takes another year or so to get the mall up to full occupancy.

Already, there are signs that recurring income from the retail segment cannot be taken for granted.

Take KSL Holdings Bhd, which owns three investment properties — KSL City Mall and KSL Resort hotel in Johor Baru as well as KSL City Mall in Klang — that contributed about 23% to total group revenue in FY2015 ended Dec 31, 2015.

In its 1Q2016 ended March 31, KSL’s property investment earnings took a slight hit with pre-tax profit for the segment falling 9.65% to RM20.8 million despite revenue rising 1.44% to RM37.29 million.

In FY2015, revenue fell 14.5% year on year to RM686.1 million while net profit fell 22.2% to RM266.05 million due to lower property demand.

Nevertheless, KSL pointed out that while property investment revenue fell 2.1% to RM155 million, the segment still posted its best results last year since the opening of KSL City Mall and KSL Resort in 2010.

“Despite the prevailing mixed sentiments in the property sector, we believe our business model of having both development revenue and recurring income is resilient in facing any economic challenge,” KSL chairman Ku Hwa Seng says in the company’s 2015 annual report.

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia on Aug 8, 2016. Subscribe here for your personal copy.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Taman Tun Dr Ismail (TTDI)

Taman Tun Dr Ismail, Kuala Lumpur

Pangsapuri Akasia, Bandar Botanic

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

Pangsapuri Akasia, Bandar Botanic

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

Pangsapuri Akasia, Bandar Botanic

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

Bandar Bukit Tinggi

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

Kawasan Industri Desa Aman

Sungai Buloh, Selangor

Sutera Heights, Taman Juara Jaya

Cheras, Selangor

hero.jpg?GPem8xdIFjEDnmfAHjnS.4wbzvW8BrWw)