A PRIVATE caveat is a formal legal notice to the world that you have an interest in a particular property or land. For example, a purchaser who has paid a deposit under a sale and purchase agreement could enter a private caveat on the land to prevent any further dealings related to the land, thus securing his or her interest in it.

1 THE PURPOSE

A private caveat is a creature of statute under the National Land Code 1965. The purpose of a private caveat includes:

i. To maintain the status quo pending court proceedings where then is a dispute over the land title or interest in the land;

ii. To protect a claim of registrable title or interest pending registration; and,

iii. To give actual notice of the caveator’s claim.

Private caveats can offer interim protection of rights to the title or other registrable interest in the land that is under dispute. For example, if there are two persons claiming interest on a piece of land, and if one has lodged a caveat on the land and the other has not, then the one who lodged the caveat will prevail, all things being equal.

2 THE APPLICANT

One can apply to the Registrar for entry of a private caveat when:

i. Claiming a land title or the right to the land title; or,

ii. When claiming registrable interest or the right to registrable interest on a piece of land.

Basically, whoever has a ‘caveatable’ interest has a right to lodge a private caveat. In order for the interest to be caveatable, it must be capable of being registered. Circumstances where a caveatable interest is present include:

i. A purchaser under a sale and purchase agreement claims a right to the land title;

ii. When there is an option to purchase under an unconditional binding contract;

iii. Once a deposit is paid; a paid deposit is sufficient to give rise to a caveatable interest even though no contract was concluded; and,

iv. Equitable chargees can enter into private caveat pending registration of the charge.

Situations such as a tenancy; the owing of the balance of the purchase price, where the option of purchase has lapsed; and where the vendor has validly terminated the sale and purchase agreement, will not give rise to any caveatable interest.

3 THE PROCEDURE

The application for a private caveat must be in Form 19B and be accompanied by the relevant prescribed fee. The application must state the nature of the claim on which the application is based on and whether the caveat is to bind the land itself or is only of a particular interest.

The Registrar who receives the application will then exercise a purely administrative function which means the Registrar would not be concerned to enquire into the validity of the claim. In other words, the Registrar has no power to reject the application of a private caveat. As long as the claim of the caveator to an interest in the land is prima facie good, the caveat shall then be registered.

4 EFFECT AND DURATION

A private caveat has the effect of prohibiting the registration, endorsement, or entry of any instrument of dealing to be executed by or on behalf of the registered proprietor. The caveat, under the Torrens system, has often being likened to a statutory injunction of an interlocutory nature restraining the caveatee from dealing with the land pending determination by the court of the caveator’s claim. A private caveat will be in force for a period of six years unless it is withdrawn by the caveator, or lapses, or removed by the Registrar pursuant to an order of the court.

5 REMOVAL

Firstly, a private caveat may be withdrawn at anytime by the caveator by submitting the necessary and required form for withdrawal. Thereafter, the Registrar shall cancel the entry of the caveat in the register document and issue a notice to the caveatee regarding the withdrawal.

Secondly, the Registrar can remove a private caveat. Only the person or body with registered title or interest can apply to the Registrar for removal by submitting Form 19H together with the prescribed fee. The Registrar will then serve on the caveator a notice of intended removal in Form 19C. The caveat shall lapse and be of no effect at the expiry of two months specified in the notice unless the caveator applies to the court for an extension order before the expiry date. In deciding whether to allow for the extension, the court will use a three-stage test, which includes:

i. Whether the caveator has a caveatable interest;

ii. Whether the caveator’s claim raises a serious question to be tried; and,

iii. Whether on a balance of convenience, it would be better to allow the caveat to remain until trial.

Thirdly, a private caveat may be removed by an order of the court. Applicants for the removal by court order could be any person or body aggrieved by the existence of the private caveat. The caveatee bears the responsibility and obligation to prove to the court that there are sufficient grounds for him or her to apply for the removal. Once the caveatee is successful in proving this, it is then for the caveator to prove that the caveat should remain by satisfying the three-stage test above.

Chris Tan is a lawyer, author, speaker and keen observer of real estate locally and abroad. He is founder and managing partner of Chur Associates.

Disclaimer: The information here does not constitute legal advice. Please seek professional help for your specific needs.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Baypoint @ Country Garden Danga Bay

Johor Bahru, Johor

Menara Bintang Goldhill

Bukit Bintang, Kuala Lumpur

Pangsapuri Akasia, Bandar Botanic

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

Pangsapuri Akasia, Bandar Botanic

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

Bandar Bukit Tinggi

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

Pangsapuri Akasia, Bandar Botanic

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

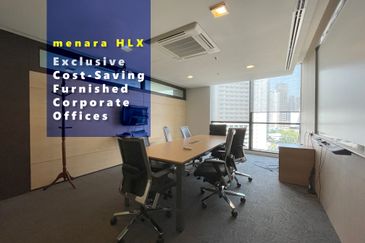

Menara HLX (formerly Menara HLA)

KL City Centre, Kuala Lumpur